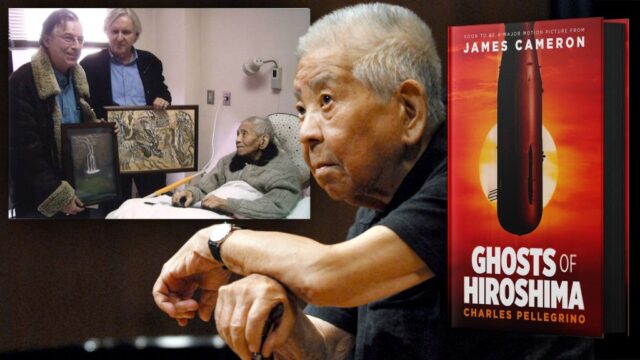

Editor’s note: While up to his eyeballs in Avatar sequels, James Cameron made a deathbed promise to Tsutomu Yamaguchi (one of the survivors of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb blast) that he will tell the story onscreen of those history-changing moments in Japan from the vantage point of the Japanese ravaged by the blasts that ended World War II.

Cameron and author Charles Pellegrino gave Deadline permission for a glimpse at a nightmare, before the book hits stores August 5.

Cameron found a way to weave in a love story that turned Titanic into at one time the biggest-grossing film of all time. There are earnest and touching characters aplenty in Pellegrino’s book, but this one plays out more like Schindler’s List than anything else. “Not since Titanic have I found a powerful, heartbreaking and inspiring real life story as found in Ghosts of Hiroshima by Charles Pellegrino. This is an amazing book and a film I am excited to direct,” Cameron says.

Read the excerpt below.

— Mike Fleming Jr.

At Moment Zero, the most important thing in the world for eight-year-old Takashi Tanemori was a game of hide-and-seek that brought him indoors while his friends scurried after hiding places among the bushes and trees outside.

In an instant, Tanemori’s classroom vanished in the purest white he had ever seen. Even with both hands closing reflexively over his eyes, he saw the bones of his fingers shining through shut eyelids, like an X-ray photograph. And in that same moment, he was cocooned and saved from harm in a tiny cave of wood and stone that formed around him near the outermost wall when the three-story schoolhouse compressed down like a big cardboard box to barely one story tall. Outside, beneath the blinding light, his friends appeared to have been spirited away.

Inside the school, history would record only one other child who lived, Mizuha Takama Kikuzaki. She was almost twelve years old on the day of the bomb.

Mizuha began to wonder how she came to be in this strange manifestation of hell.

The answer was all so painfully simple.

Defiance got me here.

She and a great many other eighth grade girls had been evacuated to a “summer camp.”

In a forested compound beyond Hiroshima, most of Mizuha’s fellow campers no longer had fathers, because the men were taken away to the Pacific War. Many of those fathers had ceased sending letters home and were listed as “missing.”

The children hated being taken away from their mothers, and they’d been more than merely turning cruel; they were being groomed specifically for savagery. Girls as young as nine and ten practiced with sharpened bamboo spears—practiced at blocking and stabbing maneuvers until those actions became muscle memory. Soldiers told the children that they must prepare for a fight to the death because if the American’s captured them, they would dissect the girls like animals, rape them, and eat them, in almost that order. (Almost.)

At night, the children were instructed to write letters home to their mothers in Hiroshima. Mizuha understood without being told that their letters would be read and “fact-checked” by the new “teachers.” Punishment would be swift and brutal if a soldier read anything indicating “bad thinking.”

“Dear Mother, I am enjoying life with my new friends and teachers,” she lied. “It’s a nice place. Please don’t worry, because I’ll study hard.” She and her friend Yasuko would write the truth later: “War plays unfair tricks with fate; it cheapens human life to the level of a worm.”

Infested with the camp’s fleas and lice, hungry and surrounded by lies, Mizuha made a prison break. If anyone thought to recapture her, there must have been too few people to spare for the chase. And so, with her mother’s blessed Lady of Mercy in mind, Mizuha reached home in two days, bowed, and prayed her thanks: “Thank you, Mary, that I’m in Hiroshima.”

###

At Mining Camp 25, where British prisoners were being worked and starved to the edge of death, it had become more widely spoken even than rumors of Hitler’s death that an airfield nearby was dedicated to the final preparation of kamikaze planes. From a hilltop at the mine, it was possible to observe the horror. The war really was devolving into the eastern Children’s Crusade.

“Such was the shortage of trained airmen,” 23 year-old POW John Baxter recorded, “that area schools were being scoured for new recruits—schoolboys were being pressed into service as suicide pilots. And we became used to the daily procession of solemn-faced youths [in] black kimonos and with sweatbands on their foreheads, preceded by a Shinto priest and an air force officer on their final journey to the waiting aircraft.” Baxter estimated the boys to be about age sixteen, but some were, in fact, as young as fourteen.

Some forty miles from the camp, beneath the target of the second atomic bomb, a conscript named Yoshitomi Yasami was already assigned to die. The sixteen-year-old had been working for weeks, deep within a huge labyrinth of interconnected factory caverns and launch tunnels, well hidden from Allied aerial reconnaissance. Yasumi handled tools and dies and lathes, producing precisely measured parts for one-way-mission aircraft. And most chilling of all were the newly arrived aerial torpedoes called Ohka, a word meaning “cherry blossom.”

Yasumi had been conscripted from the Imani Commercial School “to work in great honor for the emperor.” The latest generation of “cherry blossom planes” was advertised to the kids as fantastic rocket ships. The newer models would be catapult-launched from their hiding places, and they would be given extended range, to “greet” the American ships before the enemy could come ashore.

Those boys selected for training to fly the new Ohka designs were praised as “thunder gods.” But being revered and granted access to great food in a time of shortages did not quench their apprehension. Certain bits of information had leaked out to the cavern kids. Yasumi learned that an Ohka pilot had to be of small stature, with a shoulder width of only fourteen inches so he could fit inside the rocket torpedo. Men had measured every new kid’s shoulder width before he was conscripted and driven far from home to the tunnels. Yasumi missed his mother.

On the day of the second atomic flash, confusing radio chatter about air raid planes would precede, only by a matter of minutes, the sudden loss of power within the maze. After the whole mountain danced and swayed, after people near a tunnel entrance were seared and mauled beyond hope of survival, even before Yasumi crawled outside, the boy would realize This means I get to live.

###

More than twenty miles from Hiroshima’s Ground Zero, defiant Mizuha’s fellow inductees saw the detonation that flattened everything around her. At Moment Zero: a stupendous lightning flash in the distant blue sky, and then “far between the mountains, what appeared to be a small round cloud.” The spear-trained child Yasuko Kimura would write, “The little round cloud rose bigger and bigger, finally taking the shape of a mushroom. The mushroom—very strange—grew just like a slow-motion movie.”

Mizuha had returned to her old school and was permitted to rejoin her class. She was deep within the building when it compressed. Huge wooden beams crisscrossed and interlocked overhead and formed a protective tent around her. The wood and rubble shielded Mizuha during the critical first thirty seconds of quantum machine-gun fire—shielded her from gamma rays and volleys of neutron spray and even DNA-scrambling nuclei of iron and tungsten and fractured pieces of uranium from the bomb itself.

More than ten miles away, in the atomic strike plane, bits of strange new matter stopped and radiated inside the fillings of the captain’s teeth. He would recall that it tasted like lead melting in his mouth.

The water droplets condensing in and around the rising cloud were swirling with newly created particles that would have terrified even the bomb’s creators. And the radiating droplets returned to the streets as black rain, falling as horizontal gusts across Mizuha’s neighborhood and inflicting upward of one-third the amount of secondary radiation exposure able to kill.

Mizuha burrowed and squeezed her way to the surface about the same time as the Tanemori boy, who discovered that a few of his friends appeared still to be engaged in their game of hide-and-seek, ashed and frozen in place.

###

North, near the Misasa Bridge, two-year-old Sadako Sasaki came to be sitting in a half-sunk fishing boat while her mother and the other adults tried to bail water out. Sadako’s brother Masahiro, only four years old, tried to help. More than a dozen people, most of them showing signs of flash burns, were trying to climb into the boat. Masahiro reached out and pulled as hard as he could at a man’s hand; but a commanding voice at the tiller ordered him to stop. “You’ll swamp us if you bring any more people aboard. This is not a time for compassion. It will only get us all killed.” The boy retreated from the gunwale and sat down hard against pieces of blast-damaged wood.

From the fishing boat-turned-lifeboat, barely visible through gusts of black rain, a whirlwind of fire rose higher than the city’s tallest department store—twenty, maybe thirty stories. Another of the fiery serpents was struggling to be born along the near shore. And another appeared alongside it. And another. And another. From both sides of the river, Masahiro’s world was a gallery of impossible images. A two-story house with one side torn away had all its furnishings on display. Table settings were perfectly in place despite being completely aflame, and everything stayed intact until the entire structure leaned forward and tumbled into the water. Even when sheets of dark rain provided occasional shielding from the glare of the fires, the air remained astonishingly hot. Driven by thirst, Masahiro and his sister licked the filthy black rainwater from their lips. Its taste and smell were metallic. Yet the rain was soothingly fresh and cold and no one aboard could have imagined that it was dangerous. It seemed a wonder enough that they had survived the past few minutes at all.

###

In waste fields strung with cobwebs of downed electrical and phone lines, Mizuha recognized her father, searching through ruins near the school. She ran toward him with such joy that her campmate, Yasuko, would one day include the event in a novel-turned-film—White City Hiroshima—in which Mizuha’s own daughter (still many years from being born) would reenact this rare and fleeting moment of light in all the darkness.

Father, who had survived in a factory beyond the fires and the fallout, would have received no radiation injury at all had he not come into the zone of the black rains in search of his family and anyone else who might still be alive—no injury at all had he not joined the machinists at a trolley garage and disembarked as a wandering rescuer into the regions of deepest and still lethally young radioactive debris—again, again, again.

There could never be a proper assessment of how many different species of chromosome-shredding isotopes he inhaled, ingested, or absorbed. With each trip into the hot zone, radiation poisoning was targeting Mizuha’s father, slaying him for his kindness, for his humanity.

Mizuha would tell future generations how the Atomic Bombing Survey physicians were always seeking her out for blood samples—“but never offering medical care. Just candies.” In 1950, Mizuha knew only that her white blood cell counts continued to roller-coaster, mostly plunging down and staying down for long periods, until finally a family doctor told Mizuha that she was terminal and that medicine could do nothing to save her.

Defiance again.

By then, Mizuha had enough knowledge to navigate medical libraries with ease. She was resolved to face death along her own path, shifting toward what future generations would recognize as a vegetables-and-nuts-and-fruits-centered “Mediterranean diet,” backed up with everything she could learn about Chinese herbal and root-extract medicines, buttressed with an indomitable will.

In defiance of medical prophesy, Mizuha lived.

The doctor who prophesied her death—well, he died.

And still, the bomb’s power to harm a family had been but fractionally wielded. Mizuha found love, married, then suffered four miscarriages and a stillbirth. Each time, she survived a crippling anemia “by too frighteningly thin a margin.”

And then, while monsoons and isotope decay returned Hiroshima gradually toward normal background radiation levels, while rockets shot to the moon and Mizuha built a business that prospered, she knew, finally, the hope and joy of a pregnancy that took root—and which had progressed successfully through the first three months without degrading her blood. She assured her friends and family, “Everything will be all right.”

The doctors were not so sure. Though the space age had arrived, in 1973 there were no such tools as high-resolution sonograms and genetic testing. According to prevailing opinion, given her Hiroshima exposure, she had a 90 percent probability of delivering a significantly handicapped child. “If it survives,” authorities said.

This mathematical judgment was based almost entirely on what happened to first-trimester fetuses exposed directly to the bombs of August 1945. By 1973, the “90 percent” figure had become a self-perpetuating textbook dogma, based on supposition and fear rather than actual data.

No one in authority quite understood yet that almost all the alien-appearing fetuses in the Atomic Bombing Survey’s embalming jars had been exposed during nature’s crucial first trimester, when the genetic software that sequenced tissue layers into human beings happened to be most easily shaken up and shoved off course, to produce stillborn “monsters.”

Knowledge had been so slow to come (and acceptance of that knowledge generally slower) that among the exposed, who now called themselves hibakusha, nature’s self-correcting nucleic acid monitors were so vigilant that postwar second and third-generation children were proving the expected “monsters” was just another bit of dogma.

“Only one dissenting doctor,” said Shiho, the daughter fated to become the twelve-year-old who would portray Mizuha in White City Hiroshima, “only this one dissenting doctor—though no one knew what the outcome would be for me, and though everyone except my mother was very afraid of her refusal to abort—this one doctor said to her, ‘I know you. I see your kind soul, and if you’re going to have a child with a disability, you will take care of and you will raise that kid.’

Most of Mizuha’s family had died from the black rain, and from the loss of peace and sanity that always came with wars. “Wars take everything,” Shiho had said.

###

The history of civilization is written in humanity’s perversion of nature. In 1945, Uranium-235 was the still-active remnant of supernovae and their colliding neutron-star corpses—which gave our solar system life. Thinking creatures sought out the uranium, coaxed it to beget plutonium, and taught a dead star how to scream out against humanity—twice.