I

’ve been dreaming about the Badlands again. It’s a scorching July day in 2002, and Nicole and I are hauling ass in my VW Beetle across South Dakota. I’m driving; she’s riding shotgun, eating a Slim Jim. We’re blasting The Eminem Show with the windows down, our hair whipping in the hot desert air, when Nicole sees a sign and tells me we need to pull over.

We’ve hiked a mile or so into the moonscape of the park when we come across a pink boulder with a deep split down its center, like a giant earth vulva. Nicole grins at me, strips off her clothes, and springs onto the rock. “Take a picture,” she says, arching her nakedness into a bridge over the dark cleft. I snap a photo. She shakes her curls at me upside-down and says, “Now you.” I get undressed, climb up, and thrust my hips to the sky. She takes my picture. We’re getting dressed when a couple of hikers come around the bend, and we cackle all the way back to the car.

In the summer of 2024, I began retracing our journey on a cross-country road trip, visiting people who could help me put the pieces together, trying to remember who Nicole was before everything went wrong, since a chance encounter with seven kids blew our lives apart, with a bullet ending one life and shattering countless others. Murder doesn’t only happen to the person who dies.

It’s been two decades since the media took an incredulous phrase that fell out of Nicole’s mouth — “What are you going to do, shoot us?” — and blamed her for her own death while capitalizing on it: The Village Voice called it “A Murder Made for the Front Page.” The New York Post covered the killer’s trial gavel to gavel, while glossy magazines wrote about how not to let this happen to you.

Things have been fucked up ever since the night when I sat in a Manhattan police station trying to comprehend that Nicole was dead, and I was not. But after 20 years, I felt like I could finally revisit her story. With a therapist guiding me, I went back to the night Nicole died over and over until something shifted. It was like a foreign object had been extracted from a wound. It still exists, but it’s outside me, and I can examine it without pain. Now, I want to know how the others who loved her have coped with losing her. That’s what I’m on this trip to find out.

‘She Always Felt Like a Little Bit of an Outsider’

Nicole DuFresne was born on Jan. 5, 1977, in Wayzata, Minnesota, a wealthy suburb west of Minneapolis. Her father, Tom, was a forceful, charismatic man who worked as a commercial real-estate developer. Her mother, Linda, a knockout with turquoise eyes, was a gentle, creative woman. Nicole and her younger brother, Zach, both inherited their mother’s looks, but Nicole took after her father when it came to temperament; she was a passionate, moody kid who would dominate on the soccer pitch and then write poetry in her bedroom. “I think she always felt like a little bit of an outsider, even in our family,” Zach DuFresne tells me when I visit him at his quiet suburban home in Colorado, “but she was totally unafraid to be herself.”

DuFresne moved from Seattle to New York in 2002 to be part of the downtown theater scene. “I feel that I can be my absolute self there,” she wrote at the time.

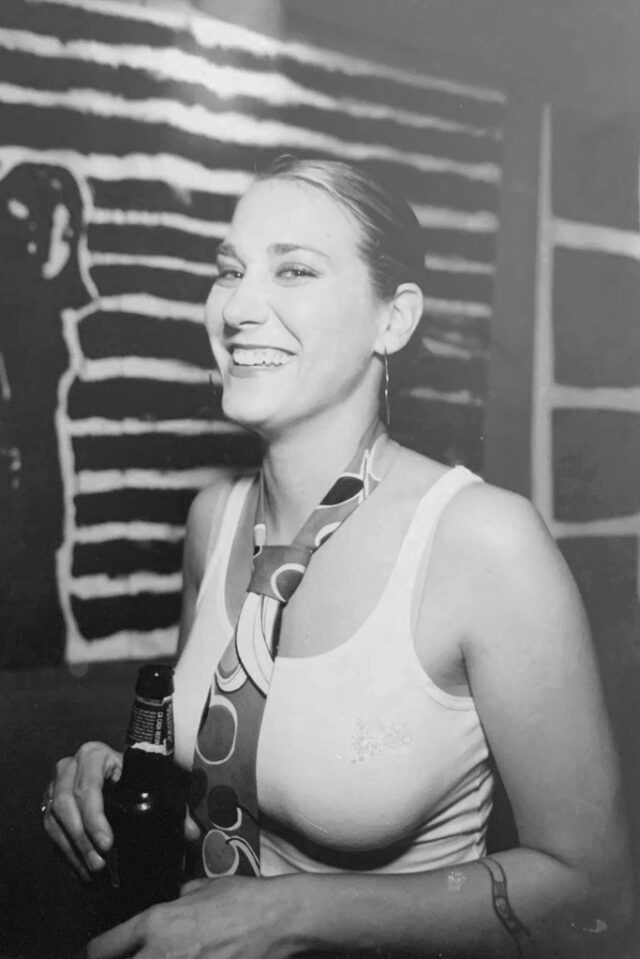

Julia Newman

Tom DuFresne wanted his kids to have the best of everything, but from a young age, Nicole bucked his attempts to insulate her with money. She hated the preppy private school her parents sent her to, and insisted on attending public school for junior high before transferring to an arts high school. When she moved to Boston to study theater at Emerson College, her father rented her a brownstone apartment in a tony neighborhood, but Nicole chafed at feeling like a rich kid. She started to work odd jobs that didn’t conflict with her schooling.

In her junior year of college, Nicole was raped in the parking lot of a bar. When she told her parents about the assault, they begged her to come home, but she refused; she’d been cast in a show that she didn’t want to drop out of. She received counseling and later used the traumatic experience as inspiration for a two-woman play, Matter.

I have a copy of the play with me on my cross-country travels. I keep returning to one line that articulates a familiar feeling: “In my dreams someone is waiting to eat me.”

Nicole and I met in Seattle at Theater Schmeater in August 2001, on the first day of rehearsal for Our Country’s Good, a play set in a penal colony in 1780s Australia. The director wanted everyone to be as disgusting as possible: lice, syphilis, scabies, goiters, rotten teeth. Nicole was good at getting ugly; her performance was frightening, “almost unbearably tragic,” one reviewer wrote. I played a convict named Shitty Meg and pushed the gross-out factor as far as I could. We bonded over the freedom we found in being filthy; our playacting felt like an antidote to what the world expected of us.

She loved that I’d worked on an Alaskan salmon boat. I was mesmerized by her witchy hippie energy, lean kinetic body, and throaty laugh. After the show closed, she asked me if I would create a show with her. We wrote a two-hander inspired by a book about CIA brainwashing experiments and hit the fringe-festival circuit in the summer of 2002.

Burning Cage was an intense play. A reviewer at Minneapolis Fringe called us “feminists with an axe to grind.” We scrawled “Come see the axe-grinding feminists!” in chalk outside of every venue after that. We did better at other festivals — one critic said our show was “precisely the kind of art and passion that fringe theatre should be about.” Another called us “balls-out brave.”

By the time we won Artistic Pick at the Seattle Fringe that fall, we’d been on the road together for most of the summer, and we weren’t sick of each other, which felt monumental to me. I’d always been reserved in my friendships, but Nicole refused to allow it. She told me I needed to trust her; I told her I had a weird feeling that things with us wouldn’t last. “It’s going to last,” she said. I chalked up my anxiety to existential dread, and we started to plan our next collaboration.

A couple of months later, Nicole and her fiancé, Jeffrey Sparks, were moving to New York, and she stopped by my place with a farewell gift — a little glass vase holding a paper scroll. She said it was a message for whenever I couldn’t reach her and needed to hear from her. I promised her I’d be right behind her; we had things to do.

Nicole was thrilled by the energy of New York. She started developing a pilot with Jeffrey to pitch to the Food Channel (Nikki’s New York), and launched herself into the downtown theater scene, painting sets at LAByrinth Theater Company while concentrating on her own undertakings with a group she’d co-founded with Emerson classmates. She worked at a nonprofit serving seniors on the Upper West Side to pay the bills. “I feel that I can be my absolute self [in New York] since there are so many different souls here,” she wrote in her journal. “They all work like a puzzle. I suppose there are many hardships I will have here, but I am excited for all the gold I could find.”

A year later, I made the trek from Seattle with my boyfriend, Scott Nath. We moved into a fifth-floor walk-up at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge, and I loved the aching feeling of climbing into the sky. We survived off cheap burgers and egg sandwiches from Mom’s Diner, and $2 PBRs from Welcome to the Johnsons; we’d peer into the window of wd~50, the city’s hottest new molecular gastronomy dining establishment, knowing we couldn’t afford to even walk inside. The grime was exhilarating, and the glamorous boutiques opening between old-world vestiges — hat stores, bridal shops — gave the neighborhood a sense of urgency. We’d wander home at sunrise past commuters making their way to the train as we crawled into bed.

Nicole and Jeffrey had us over for a welcome dinner, and she gave us a bag of weed mixed with lavender. “You’ll need it,” she said with a laugh. She told me I should get new headshots; she’d just had hers done, and was insistent that we both had to step up our game. The following months were a glorious whirlwind of auditioning, acting, and writing. Nicole was producing new work with her theater company; I was making a living as an actor. We met up to write whenever we could, ginning each other up as we brainstormed ideas and to-do lists. We laughed so much: I can still hear her bellowing “I have to pee like a horse!” as she charged into Cafe Mogador after being stuck on the L train for an hour.

Nicole’s fiancé, Jeffrey, saw his grief turn to anger after her death. Now, he aspires to be a good father in her honor. “I liked her vision of me,” he says.

Courtesy of Jeffrey Sparks

Reading through our notebooks, I’m struck by how relentlessly confident we were in ourselves, and each other. By the time we rang in 2005 at a warehouse party in a dilapidated former church — the kind of sweaty all-night revelry I’d always dreamed of going to — I felt like we could take over the world.

‘They Were So Happy, It Made Me Angrier’

Rudy Fleming was born on June 23, 1985. His family lived in the West New Brighton housing projects in a bleak part of Staten Island where more than 15 percent of the population lived below the poverty line. Violence was a grim reality in the Fleming household; his father was shot and killed when he was a child; an older brother was given a five-year sentence for assault; another was sentenced to eight years in prison for beating a man with a baseball bat; and a third was shot and killed with his own gun during a botched robbery.

Fleming struggled with anxiety and depression from a young age, according to court documents; he was diagnosed with a learning disability at the age of eight and enrolled in an individualized program by the Department of Education, but there’s nothing on the record to indicate that he received any psychiatric help. In 2001, when he was 16, Fleming pulled a gun on truancy officers who picked him up for loitering. According to the police report, which designated him an emotionally disturbed person, he told arresting officers, “You should have shot me. I want you to kill me. I want to die.” He received a three-year prison sentence on a weapons charge and was sent to an upstate correctional facility more than 200 miles away.

At an April 2004 parole hearing, he said prison had taught him to learn from his mistakes. That June, three days before his 19th birthday, Fleming was released on parole.

In January 2005, Fleming moved into the apartment of his godfather, Servino Simmon, in the Baruch Houses on the Lower East Side, a sea of tan high-rises overlooking some of the most expensive real estate in the country. Fleming had grown up close with Simmon’s kids — Servisio, who was 21 years old, and Servano, who was 17 — and they were living there, too. Fleming’s 18-year-old girlfriend, Ashley Evans, a well-liked high school cheerleader, also moved into the apartment.

On the night of Jan. 26, 2005, Fleming, Evans, Servisio, and Servano, along with their 18-year-old cousin David Simmon, David’s friend Kayshawn Boyd, 15, and Boyd’s 14-year-old girlfriend, Tatianna McDonald, were hanging out at the apartment, smoking weed, drinking, and playing with Fleming’s gun, which had been stolen from its legal owner in South Carolina in 2002. It’s unclear who Fleming got it from or how long he’d had it, but he liked showing off the heavy silver six-shot .357 Magnum revolver, spinning the chamber, loading and unloading it. Servano thought the gun was cool, too; at one point, he and his brother played a mock round of Russian roulette without pulling the trigger.

That same night, Nicole was working her first bartending shift at Rockwood Music Hall, a new venue on the Lower East Side. Scott and I met up with Jeffrey at the bar to celebrate her new gig; Nicole served us a couple of rounds, and when she finished her shift, the four of us went to a raucous hipster joint called Max Fish, where we ordered rum and cokes and played pinball.

After a few hours at the apartment, Fleming and his friends were bored, so they went out to “start trouble,” McDonald later said. They were walking toward the Delancey-Essex subway station when they passed 22-year-old security guard Adam Chavez coming home from work. Chavez was wearing a white leather jacket that caught Fleming’s eye. He chased after Chavez with David Simmon and Boyd, who punched him and demanded he give up the jacket, but after Fleming whacked him twice with his gun, Chavez managed to pull away and run into the street in front of a passing taxi. He called 911, but by the time cops showed up, the friends were on a train to Brooklyn. Chavez declined to file a police report and headed home.

The friends took the J train through the rooftops of Brooklyn and got off at Broadway Junction, deep in the borough. They hung out on the subway platform, where the boys tried to goad Evans and McDonald into fighting a couple of other girls waiting for the train. When they refused, the guys made fun of them for chickening out, so when they caught a train back to Manhattan, the girls said they would fight anyone they pointed out. They got off back at the Delancey-Essex stop around 3 a.m. A surveillance camera outside Schiller’s Liquor Bar captured the group walking east on Rivington toward Clinton.

We had left Max Fish a few minutes earlier. We were buzzed, goofing around, pushing one another into snowbanks — oblivious gentrifiers on the home turf of seven friends out looking for a fight. When Evans heard us laughing as we crossed onto Clinton Street, her resentment flamed. “They were extremely happy, so that made me even angrier,” she later told the police. Pissed off, she pointed us out to Fleming as the ones they should fight. Then everything happened fast.

By the time we rang in 2005 together at a warehouse party, I felt like we could take over the world.

I remember being stopped. Shoved against a wall with a gun. My purse is yanked away. A loud bang. Scott running, screaming, “Murderer! Murderer!” Nicole on her back in the street. My bare knees on cold grit as I kneel next to her. She’s looking up at Jeffrey as he leans over her, telling her to stay with him. The headlights of cars coming toward us off the Williamsburg Bridge. Then I’m in the back of a cop car, looking at Scott’s crumpled face in alternating red and blue light.

According to witnesses who later testified in court, Fleming stepped in front of us, pulled out his gun, and told us to give him our money. Scott said we didn’t have any because we’d spent it all at the bar. When Jeffrey tried to push past him, Fleming smashed him in the face with the gun, opening up a gash over his eye. Then, as Nicole went to check on Jeffrey, Fleming slammed me against a security gate with the gun. He yanked my bag away and threw it to Evans and McDonald as Nicole approached him and pushed him, saying, “You got what you wanted.” Then, according to testimony from McDonald and Servano Simmon, she asked him, “What are you going to do, shoot us?” Fleming lifted the gun, pointed it at her chest, and fired. Nicole stumbled and fell into the street as they ran. The bullet had pierced her heart.

Cops took us to the 7th Precinct station, where Scott and I waited in an interview room under buzzing fluorescents for what felt like hours until Jeffrey came back from the hospital and told us Nicole was dead. He went into another room to call her father. I remember hearing him howling.

When we left the station on the morning of Jan. 27, I couldn’t believe the sun was shining; it was like the world had changed shape, and no one had noticed. Scott and I went home, pulled the blinds, and lay beside each other in the darkness, not talking. At some point, I remembered her message in a bottle. I got it down from my bookshelf and unfurled the scroll. It said:

Believe in yourself like I believe in you.

Sending you lots of groovey love vibes.

Have faith.

Listen to yourself.

With love,

xo Nicole

‘Becoming One of New York’s Super-Victims’

“She died in my arms.” That was Jeffrey’s heartbreaking statement to a reporter who tracked him down after a police bulletin about the shooting went out that day. The story electrified the media; the New York Post ran a cover story with Nicole’s headshot under the headline “Beauty Slain.” A photo of Jeffrey, bloody from being pistol-whipped, accompanied the accounts of her murder.

Reporters were waiting at LaGuardia Airport for Tom and Linda DuFresne when they flew in from Minnesota to identify their daughter’s body; members of the media camped out on our doorstep to snag a photo of Scott and me looking pale and shell-shocked. It was surreal to read tabloid accounts that the gun had been aimed at me too, that Scott thought he had heard it go off. My reality was fracturing.

Before internet ubiquity as we know it existed, the story of her death went viral; Nicole’s face was on newsstands across the country, and every major media outlet showed up at her memorial. The Village Voice noted that “DuFresne is on her way to becoming one of New York’s super-victims.”

The narrative in the press was initially sympathetic to Nicole, but that soon shifted.

New York Post

Surveillance videos and tips led to the seven friends being apprehended within days. The tabloids made hay in the wake of their arrests, branding them “thugs” and “fiends.” The report that our laughter had angered them was shocking; “Nicole Died for Smiling — ‘Slay’ Creeps Picked on Happy Victim,” one article blared. A photo of Fleming sobbing in the back of a police car after his arrest ran under the headline “He Cries for Himself.”

I hadn’t heard Nicole say anything to Fleming, but police told reporters that bystanders had heard her say something to the effect of “What are you going to do, shoot us next?” When Evans was arrested, she said Nicole had been the aggressor, claiming that Fleming shot her only because he’d slipped after she pushed him. Evans was accused of taking the murder weapon back to the Simmon apartment, where police had found it hidden under a bed.

After Evans’ allegation was reported, the media narrative shifted — now Nicole’s death was her fault because she’d “dared” Fleming. Safety advocates said that Nicole’s “defiant” stand had prompted Fleming to shoot her, and the National Crime Prevention Council circulated a memo on how to survive a mugging, advising potential victims to “stay cool and comply with robbers.”

The Stranger, a Seattle alt-weekly, ran an anonymous letter addressing Nicole that read, in part, “It seems you misplayed your role as mugging victim. This was not street theater you were involved in. It was real-life drama, which you helped turn into a tragedy.… Your last words suggest you did not understand the material. I’m sad that you will not get another audition.”

Cosmopolitan published a feature titled “How Not to Let Your Fearlessness Go Too Far” with tips on what not to do when held at gunpoint, next to a list of mistakes that Nicole had supposedly made.

Richard Price wrote an acclaimed novel, Lush Life, in which he echoed her purported last words; after a long night of drinking, a would-be writer is gunned down when he makes the dumb decision to tell a mugger “Not tonight, my man.” An episode of Law & Order: Criminal Intent ripped the story from the headlines. In that version, it was the friends who’d set her up.

Even after all of these years, the story has stuck. I’m listening to one of my favorite podcasts on my road trip when they bring up Nicole’s murder. “She got in their faces,” one of the co-hosts says. “Like, just give them your purse … don’t start an altercation.” Tears fill my eyes; I have to pull over. Nicole was fiercely protective; she was upset; her death wasn’t her fault. Fleming was an angry kid with a gun that he wanted to use. Maybe Nicole would be alive if our laughter hadn’t filled Evans with rage, if Fleming had gotten the help he needed at school, if the gun had gone off when he pushed me instead. Her murder was a senseless act of violence. Speculating about a different outcome only intensified the pain.

‘A Young Person Who Cannot Come to Grips’

Fleming did not respond to multiple attempts to contact him for this article; neither did any of the other six friends, who would now all be in their thirties or early forties. I want to ask them how their lives have been since the night our paths crossed; what details have stayed with them; how their age and maturity have shaped the way they think about the events of that night. But the only update I get is from Detective George Taylor, the lead investigator on the case, who tells me that he saw Servano Simmon a few years later; the only one not charged, he’d straightened his life out and was attending college.

Fleming was charged with first-degree murder. He’d exhibited bizarre behavior when he was arrested, mumbling, stuffing paper towels in his mouth, and going limp in the interview room. He was admitted to Bellevue Hospital and held under observation for several months. In a pretrial hearing, Fleming’s attorney, Anthony Ricco, told the judge that Fleming was mentally incompetent; evidently, he was hearing voices telling him not to eat and hallucinating a giant marshmallow man. However, a court-appointed psychologist and psychiatrist testified that Fleming had gained eight pounds while under observation and that his symptoms only appeared when he knew he was being watched. Although Fleming had “fewer resources than most individuals” to cope with the stress he was under, including a lack of family support, they believed he was feigning his symptoms. He was found competent to stand trial.

Fleming never appeared in the courtroom at his trial; he was removed before jury selection after an outburst that required several officers to restrain him. Assistant District Attorney Robert Hettleman called it a “well-timed action” for someone trying to avoid trial, and the judge agreed, ordering a CCTV video feed to be set up so Fleming could watch the proceedings from his holding cell.

Rudy Fleming was convicted of murdering Nicole, and is serving a life sentence. His 2010 appeal was denied.

© Bryan Smith/Zuma Press

McDonald testified that Nicole’s shooting was intentional: It had nothing to do with Fleming being pushed, she said. Scott and Servano Simmon also testified that Fleming had shot Nicole from an arm’s length away. Jeffrey testified that, although the shock of being pistol-whipped had dazed him, his memory of holding Nicole as she lay dying in the street was crystal clear. When I was called to the stand, I could only share my scattershot version of the encounter. It didn’t matter; witnesses confirmed that Nicole had been executed at point-blank range.

On Oct. 12, 2006, the jury found Fleming guilty on nine counts, including first-degree murder, robbery, and criminal possession of a weapon. No family or friends had ever come to support him. At his sentencing, his attorney asked the court for mercy. “People rehabilitate themselves, and that’s my hope for Rudy Fleming, who’s in the back, cowering in his cell,” Ricco said. “He’s a young person who cannot come to grips.” The judge deemed Fleming a “cold-blooded, thoroughly amoral killer” and gave him life without parole. The Post got in one last dig when Jeffrey told a reporter outside the court that he was relieved Fleming hadn’t received the death penalty. The headline read “Fiancé’s Pity Is Misplaced for This Vermin.”

Evans and four of the others took plea deals. Servisio Simmon received a sentence of 10 years for first-degree robbery; David Simmon was sentenced to six years for first-degree attempted robbery; Boyd was referred to family court; McDonald was adjudicated a youthful offender and received a sentence of one to three years for first-degree robbery. At her sentencing, when Evans entered a guilty plea to first-degree robbery, she apologized to the DuFresne family. “If I could take it all back, I most sincerely would,” she said. Linda DuFresne replied, “Ours is a sentence of life without Nicole.” Evans got six years. Fleming appealed his sentence in 2010. It was denied.

‘Nothing More Precious Than Time’

I went back to my restaurant job a couple of weeks after the murder. A co-worker asked me what Nicole had said to make the kid shoot her. There was a faraway ringing in my ears as someone else said, “Leave her alone, man.” I was refilling the owner’s coffee when he grasped my wrist and said quietly, “Survivor guilt is a real thing.” I knew that his parents were Holocaust survivors, so I nodded at him mutely and went to the bathroom to scream into my latte-stained apron. A few weeks later, I terrorized an elderly Weight Watchers leader after our weekly meeting by telling her what had happened and that I wasn’t OK. She patted my hand and told me I shouldn’t come back until I felt better.

When I went to collect my wallet from One Police Plaza, they handed it to me in a plastic bag labeled “Homicide Evidence.” A letter arrived from the New York State Office of Victim Services offering me funds for therapy. I thought it was pretty funny that I was a state-sanctioned victim. Nothing felt real. I couldn’t sleep. I started drinking to anesthetize myself, making it most of the way through two bottles of wine before stumbling into bed around dawn. When I did sleep, I had nightmares. My relationship with Scott started to suffer. But I kept telling myself I was OK; I wasn’t the one who died.

For years, I tried to articulate how I felt, but I couldn’t find the words. At one point, I took a solo-performance class, thinking I’d write a one-woman show about — murder? Gun violence? Grief? I can’t remember, but the teacher told me I wasn’t ready to address my experience. At the time, I was furious, but years later, I’m thankful for her candor. She was right; I needed time.

My first stop on the road trip is in Denver, where I spend a sunny afternoon with Zach, his wife, and their two kids at a neighborhood swimming pool. As we listen to the splashing of happy children, Zach and I reminisce about the Thanksgiving dinner we had with Nicole in 2004, when the siblings walked home across the snowy Williamsburg Bridge after dinner at our place. They stopped to call Linda and sing “New York, New York” to her from the middle of the East River. It was the last weekend he had with his sister.

After the trial and sentencings, a noose of grief tightened around the DuFresne family. Although Linda continued to set a place for her daughter at the table at holiday gatherings, Zach says that no one spoke her name: “My mom never recovered, and part of my dad died when Nicole died.” Tom has been in a care facility since suffering a debilitating stroke several years ago; Linda has Alzheimer’s-related dementia, and lives in a nursing home not far from Zach.

“I remember trying to see if that sadness was still there, and I was like, ‘I don’t need to dig in. It doesn’t help me move forward.’”

Linda meets me in the lobby when I pull up for our visit. She’s frail, wearing a back brace, and her face is stamped with pain, but her eyes are bright. We go to a restaurant, where we order wine and sit on the breezy patio. She asks me what I’m working on. I take a deep breath, and tell her I’m writing about Nicole. “She’d be happy that you are,” Linda says. Then she puts a hand on my arm and asks me to tell her about the night her daughter died. I tell her what I remember, and we hold hands in silence for a long time.

Later, over dinner, Zach tells me that substance abuse dominated his life for years after Nicole was killed. One night, when he was drinking with friends, one of them said something about her that set him off; Zach got into his car in a rage and drove into the side of a mountain near Aspen. “I was fucking annihilated,” he says. “I should have died.” He credits marriage and fatherhood with averting him from his path of self-destruction. Now, his family celebrates his sister’s birthday every January. “We bake a cake and tell stories about Nicole,” he says. “I’m trying to give my children some sense of their auntie.”

Next, I visit Jeffrey in his Midwest home. Over coffee in his backyard, he tells me about proposing to Nicole. They were on a road trip to Joshua Tree. “I had this overwhelming feeling that I wanted to spend the rest of my life listening to her,” he recalls. “She was sitting next to the fire. I got down on my knee, and she starts throwing all these ‘What ifs?’ at me, like, ‘What if I get a terrible disease and lose my hair?’” His answers came easily. “There wasn’t anything I felt we couldn’t handle.” She said she would marry him on one condition: that they move to New York.

After she was killed, Jeffrey’s grief coalesced into anger under relentless scrutiny from the media: “I was a pressure cooker of rage, trying to keep the lid on.” He went to the Middle East to work on a documentary about war widows, where he was held at gunpoint more than once. Danger felt comforting to him; at one point, he was riding in a car that narrowly missed hitting an oncoming truck. “I remember this distinct feeling of water washing over me,” Jeffrey recalls. “Like, ‘Here it comes.’ And I felt myself smiling.” Now, he aspires to be a good father to his 13-year-old son in Nicole’s memory. “I channel my love into being the person that she envisioned me to be,” he says. “I liked her vision of me.”

A few weeks later, I meet Scott for dinner in Brooklyn; it’s the first time we’ve seen each other in years. We stayed together until 2013, and had plenty of good times, but we had stared at each other through hell and couldn’t make it work for the long haul. We order pizza and cocktails, even though Scott doesn’t drink much anymore. He tells me that he didn’t feel the need to self-destruct like the rest of us because his testimony helped secure Fleming’s conviction — and because he entered therapy right away. “I remember trying to see if that sadness was still there,” he says, “and I was like, ‘I don’t need to dig in. It doesn’t help me move forward.’” Nonetheless, Nicole’s murder changed his trajectory; he gave up on his dream of being an actor, and took a corporate job. Since the night Nicole died, he often thinks about how limited his time is. “There’s nothing more precious than that.”

I can see how my PTSD has played out through guilt, dissociation, and self-annihilation, but I didn’t have clarity until recently. After Scott and I split up, I moved on to bad relationships with men who gave me the affection I felt I deserved, which was none. For years, happiness felt like a harbinger of bad things to come; feeling anxious and miserable was familiar. But when my last relationship flamed out, a friend recommended a form of trauma therapy called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR. After several sessions, I felt I could finally write about Nicole, as I’ve wanted to do for so long. It feels good to revisit our work, to read her journals, and to drive for days, thinking about my gorgeous, funny, wild friend without feeling suffocated. Instead of dwelling on how she died, I’m remembering how brightly she lived. I can see Nicole standing in the doorway of my apartment on the night she came to pick me up for a Halloween party wearing a slinky champagne-colored dress, smoky glitter outlining her blue eyes under a cascade of curls. I asked her what her costume was. She winked at me, and said, “I’m a dream.”