In the video, a man putters up and down the street carrying a pitchfork, shouting at his neighbors and at no one, punctuated by the occasional obscenity. He isn’t happy that the neighbors are filming. “You guys are taping me? For what?” he asks. “I’m walking down the street! I’m rehearsing! I make movies, man! I’m rehearsing a scene.” During the four-minute, 30-second clip, later shared with local TV news stations in San Antonio, the man mentions police visits to the neighborhood, which had been frequent. He references arson. He hints at a dispute that runs way deeper than this one moment, then claims he has done nothing wrong. “I can yell. I can scream. I can pray,” he says. “Whatever I want.” Separated from the phone recording him by a spearlike black fence, he departs with his pitchfork still in hand. “Keep filming me, boy. Boy,” he says. Bleep. Then the video is over, and he is gone.

He told no lies about who he was. Jonathan Joss had done big things in Hollywood. He was best known for voicing John Redcorn, a recurring character on the Fox animated sitcom King of the Hill, which ran from 1997 to 2009, and has a reboot scheduled for release Aug. 4 on Hulu, in which Joss is set to return. He also appeared in five episodes of the NBC hit Parks and Recreation as Chief Ken Hotate, a Native American tribal elder, as well as in films like True Grit and The Magnificent Seven. But that night, after filming had ended, another neighbor encountered him outside his San Antonio home. The man shot Joss dead.

The next day, Joss’ husband, Tristan Kern de Gonzales, issued a statement: “We were harassed regularly by individuals who made it clear they did not accept our relationship,” he wrote. “Much of the harassment was openly homophobic.” And so, he argued, was the shooting. The couple had been living in hotels after a January fire burned down Joss’ longtime home, and had arrived that afternoon just to check the mail. They found a dog’s skull and harness “placed in clear view,” Kern de Gonzales wrote, and deduced it was one of their pets — taunting them, they believed, for the fire, which killed Joss’ three pups. Before pulling the trigger that night, the neighbor, later identified as Sigfredo Ceja Alvarez, also “started yelling violent homophobic slurs at us,” Kern de Gonzales alleged. Ceja Alvarez raised his rifle and aimed toward the couple. Joss pushed his husband out of the way and was hit. He later died at the scene. “He saved my life,” his husband wrote. Ceja Alvarez, according to the police report, told the first officers to arrive, “I shot him.”

In part because the shooting took place on June 1, the first day of Pride Month, Joss’ death became more than a news story. It became a cause. It embodied the worst fears of the queer community, who saw confirmation of homophobic violence growing more mainstream. But almost as quickly, a counter-narrative emerged. A man who was not killed for being gay, but for being intolerable, and according to some, even threatening. “Everyone has made a judgment based on information that contradicts every known fact,” one observer wrote on Facebook. “Before you start screaming ‘hate crime,’ spend 5 minutes looking into the past 3 years of his life.” Each perspective was shaped by limited information, snippets of a life reduced to headlines. But conversations with people who knew Joss reveal a complex person whose death defies an easy explanation. Jonathan Joss was a devoted friend and partner to his husband, and he struggled with addiction and mental health. He was engaged with his fans, and prone to violent verbal outburst and erratic behavior. He was an attentive friend and a difficult neighbor. He was entrepreneurial, and an accomplished professional — but unpredictable. Chaotic.

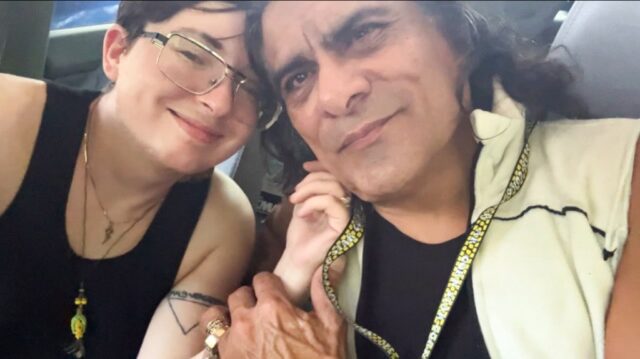

Tristan Kern de Gonzales (left) with Jonathan Joss.

Courtesy of Tristan Kern de Gonzales

So much so that when Brandy Wahl-Trejo, a longtime ex-girlfriend, learned that he had been killed, she wasn’t surprised it had happened. “I was surprised,” she says, “that it took this long.”

WAHL-TREJO HAD DATED JOSS for 13 years, starting in 2006, she says, when she visited a friend who lived in Joss’ neighborhood. The first time she saw him, Joss was wielding an ax, trying to chop down a neighbor’s fence. Wahl-Trejo believed him when he told her the neighbor was running a chop shop in their yard. His mom lived with him, he said, and it was keeping her up at night. Wahl-Trejo was 28, using meth, and ready to believe anything. She says Joss was a regular meth user then, too.

“I’ve got $5,000,” Wahl-Trejo remembers Joss telling her that same day. “Want to go to Vegas?” They stayed at the Hard Rock Casino. They gambled and attended a marijuana convention. And when it was over, she followed him to the Viejas Reservation outside San Diego, where they stayed with some of his friends. Within a week, she says, Joss got them kicked out. “He gets loud and wants attention and starts stirring up trouble,” she says. But she also loved that he didn’t judge her. That he could make her feel at ease with herself and her past. “He could make me smile when there wasn’t really a lot of reasons for me to smile.”

They set off for his houseboat in Marina del Rey, two hours up the coast. During the drive, Wahl-Trejo says, Joss’ continued meth use sparked hallucinations and frantic yelling. She remembers pulling over at a psychiatric facility. “I don’t know what’s wrong with this guy,” she says she told them. “Y’all need to help him.” But Joss instantly transformed. “He sat there and put on his best act, like he was a good boy,” she says. “And they made me feel crazy.”

She kept going on their road trip because she’d never seen California, nor the new life it promised. Joss made her feel good about herself. He made her smile. And the world he brought her into may have been volatile, but it was also novel and exciting and, eventually, downright life-affirming — even if the houseboat was disappointing, especially for a man of his credentials. “It looked like the dinghy of the boat in front of it,” she says.

The Jonathan Joss origin story Wahl-Trejo cobbled together, over time, goes like this: Joss grew up in San Antonio, born to parents of Comanche and White Mountain Apache descent, and worked in their restaurant starting in middle school. To make it a bit more fun, he inhabited different characters to wait on different tables, which unlocked his love of acting. He would tell her that his parents never took his professional acting ambitions seriously, which bugged him, because he wanted nothing more than to make them proud. He graduated from a local Catholic university in 1990 with a degree in theater, and by 1994, he’d appeared in Walker, Texas Ranger. It’s remarkable, Wahl-Trejo admits, what he was able to achieve at a time when very few Native American actors got big opportunities. And she’s not the only one who thinks so.

“Jonathan was one of the very few actors who up-and-coming Native people could look up to,” says Tafv Sampson, a Native actress whose father, Tim, lived for a time on Joss’ houseboat. “He’s kind of an icon in that way.” He was even rarer in the sense that some of his contemporaries from the 1990s, legends like Graham Greene and Wes Studi, weren’t showing up in comedies, and here he was in 1997 getting cast in the latest Mike Judge animated project. “The only roles really available at that time were the stoic Indian, the warrior, the savage,” Sampson says. “And Jonathan got to be a cartoon character. That was really rare back then, to be able to play and poke fun and make Rez jokes, and sort of be the lonely voice in the room bringing that comedy in.”

Mike Schur, the acclaimed co-creator of Parks and Recreation, also remembers Joss as “an actor that you never had to explain anything to.” He was always funny, and always a professional. He was first recommended to Schur by Parks and Rec co-creator Greg Daniels, who had worked with Joss on King of the Hill. Daniels had no hesitations, as far as Schur recalls, and thought he’d be a perfect fit for the role of John Redcorn. Joss once told Schur that he really liked the fact that his character on the show wore a suit, because all his past characters wore more traditional, more cliché Native costumes. “He really liked that,” Schur says. “That was meaningful to him.” Schur never had any trouble with Joss on set, and doesn’t remember anyone else who did, either. After Joss died, a group text among former cast and crew flooded with only fond memories. “He was just lovely,” Schur says. “He just was a lovely part of the show.”

Joss’ signature role as John Redcorn on King of the Hill began in Season Two, after the character’s original voice actor died in a car accident. Joss would go on to perform in the Red Corn Band, an acoustic, bluesy group which released its first album in 2004. Joss loved the Redcorn character, Wahl-Trejo remembers, even though he felt self-conscious about the fact that he was a replacement actor. “He never felt like he deserved any kind of recognition for what he did, yet he wanted recognition for what he did,” she adds. “He was just so conflicted and at odds with himself.”

That inner conflict could spill out in explosive ways. Wahl-Trejo says she got sober in 2007; Joss, as far as she knows, never did. During filming for his role as Denali, a rogue Comanche assassin in Antoine Fuqua’s 2016 remake of The Magnificent Seven, cast members were given slushies during breaks. Wahl-Trejo, who was on set with Joss, remembers him losing it when Denzel Washington got two, and he only got one. When he was told second slushies were “only for the main cast,” he “flipped out,” she says, and took off on foot down a dirt road in Louisiana, in costume, bound for nowhere. His volatile behavior was even worse at conventions, which became a major source of his income. “I cannot tell you how many comic cons we have been uninvited to because Jonathan just acts crazy,” Wahl-Trejo says. “If he would have just acted right, he would have gone so, so far. Jonathan was his own worst enemy.”

Jonathan Joss and Brandy Wahl-Trejo dated for 13 years.

Courtesy of Brandy Wahl-Trejo

Joss’ self-destructive instincts, Wahl-Trejo says, were at their worst in his dealings with neighbors. “He terrorized that neighborhood,” she says. Once, when his neighbor from three doors down — Ceja Alvarez, who would later be accused of his murder — installed a fence for Joss’ next-door neighbor, Joss claimed it encroached an inch and a half onto his property, Wahl-Trejo remembers. He responded, she says, by dousing the fence with red paint. And in an area where many of his neighbors were Latin American, Joss, Wahl-Trejo adds, had a habit of using racist insults. He’d call people names, threaten to get their kids taken from them. Kern de Gonzales offers a different perspective rooted in context. “If he ever said something in anger, it was in response to being verbally attacked,” he explains. “Jonathan did not have xenophobic beliefs. He believed no human was illegal. He told me that many times, and it came from a deep understanding of what it means to have your very existence questioned.”

Nevertheless, Wahl-Trejo argues, Joss was often to blame for the conflict. Back when they were still together, sometimes he’d go out of town for work, and she’d stay in the house without him. The difference, she remembers, was obvious. “Everybody could relax. Everybody didn’t have to stay inside,” she says. “And then he would come into town, and everybody would have to stay in their houses because he would just act like an asshole.”

Other neighbors told a nearly identical story. “They don’t know what we went through,” Alejandro Ceja, a relative of the shooter, told the San Antonio Express-News. “We were afraid — all the time.” Another neighbor alleged in the same story that Joss would often run around brandishing weapons, including a machete and a tomahawk he liked to throw at telephone poles. Joss’ shooter, in a June 2024 police report, claimed Joss had driven past his house waving a crossbow and hurling racial slurs. Multiple neighbors reported Joss to police for damaging their fences with his Hummer. “Everyone can try to judge me for what I have said about my neighbor,” one person wrote on Facebook, “but y’all didn’t live next to him and witnessed everything he did.” Ceja Alvarez, the shooter, echoed Wahl-Trejo’s recollections from 2006 in police reports: Joss would put on an act when police arrived, then resume harassment after they left. Reports documented Joss driving by Ceja Alvarez’s house threateningly, once saying he was “coming for him.”

Josh Long, a local San Antonio friend who met Joss at a comic con roughly 15 years ago, remembers visits where Joss would gallop out the door when certain neighbors walked by, sometimes provoked and sometimes not. He’d yell at them to get away from his property, and from Long’s car. “He’d come back all winded and mad,” Long says, “and you could see the anger in his face.” Joss, he adds, is best described as a “force of nature” — for better and worse.

Josh Long met Joss at a Comic Con. They both lived in San Antonio, and became friends.

Courtesy of Josh Long

Wahl-Trejo left Joss in 2019, after which he got married to a different woman in 2020; then divorced in 2023; then married again, this time to Kern de Gonzales, a trans man, after coming out as gay. All the while, despite the difficulties, Wahl-Trejo always felt indebted to Joss. She was a girl from the south side of San Antonio, and because of him, she got out and grew into her full self — and had an awful lot of fun along the way. “I would have never been able to meet Chris Pratt or Amy Poehler or Josh Brolin. Brittany Murphy was, like, my friend. All these things would have never, ever happened if not for Jonathan,” she says. Even her sobriety, she owes in part to her time with him. To the world he opened up for her. “That’s what kept me around so long,” she adds. “I felt like I owed him something in life, because I felt like he gave me my life back.” At the end, though, her purse of forgiveness had finally been emptied.

The last time Wahl-Trejo saw Joss was a few months before the shooting, when she happened to be in his neighborhood. She drove by his house and found Joss outside, in his underwear, with an arrow in one hand and a pan in the other. “I didn’t stop and talk to him,” says Wahl-Trejo. “I just kept going.”

COURTNEY LYNN SENT JOSS A a Facebook friend request back in 2016. She didn’t expect him to respond — but he did, almost right away. She’d been a fan of his work, from King of the Hill to Tulsa King, but starting then, she became a fan of his person, too. Joss was a prolific poster, livestreaming videos and sharing updates about his daily life on a near-constant basis. The messages offered any fan’s dream: a window into his existence. But Joss wasn’t posting for branding alone. He cherished those fan interactions. And many of his fans likewise cherished him. They never saw the side of Joss that Wahl-Trejo and his neighbors describe.

After Joss’ death, hundreds of his fans flocked to Facebook to offer condolences. Some of them had known him personally, but many did not. Some lamented not being able to meet him in person. Others talked about how he still had so much to give. “I can’t believe this is true,” one wrote. “I was so excited to meet you one day.”

Lynn was yet another voice in the chorus. Her connection to Joss, she explains, grew in 2023, when she re-joined TikTok. He followed her, and messaged her randomly with a “Hello” and a waving sticker. They chatted briefly over DMs, but never really talked until shortly before Joss’ house burned down in January. He’d been trying to sell his very own “King of the Grill” spice blend — an idea hatched back in 2011 with his longtime friend and collaborator, Robert Rios. He’d sold many things on Facebook, from T-shirts to headshots to personal videos, often corresponding with buyers through his personal phone number. Lynn reached out to place an order, and Joss video-called her right away. Joss told jokes in his John Redcorn voice and was nothing but pleasant. Later, they talked more over text. “He was definitely somebody who was going to speak his mind and tell his truth, and he wasn’t afraid of what other people thought,” Lynn says. “I liked that about him.”

Joss, in general, showed up for his friends — digital and nondigital alike. Like Patrick Zachary Cortez, who remembered him in a Facebook post as a childhood friend, someone always willing to help or to call him up at random hours for “hilarious diatribes,” and for generally being “kind, giving, respectful, articulate, well-mannered and sweet.” Likewise, Rios remembers Joss as smart and welcoming. He was happy to talk to anyone, fans and friends alike. “He knew a lot. He would teach you a lot,” Rios says. “He would stand out. He would take over. Very lovable. Very gullible. And he could get by on a dollar any day of the week.”

Patrick Zachary Cortez and Joss had been friends since childhood, and worked together on several business ventures.

Courtesy of Patrick Zachary Cortez

Long, the friend who met Joss around 2010, remembers hanging out with him last year — one of his last visits before Joss died. Long had just lost his job and was feeling down. Joss invited him over, cooked up some homemade chalupas, and joked about how they were eating “tapas” — “you know,” Long remembers Joss saying, “the Spanish word that white people call broke Mexican food.” Long chokes up at the memory. “The good times around Jon were really good,” he says. “And then the bad times were sad, watching from the outside, wondering what he was going through.” Long insists he never saw Joss so much as drink around him, but he suspected his friend was drinking or using substances, just given the emotional roller coaster he appeared to be on from one visit to the next. That, and what seemed to Long to be an accelerating waste in his face.

Trey Brown, a King of the Hill superfan with a Hank Hill tattoo on his thigh, knew nothing of Joss’ struggles when planning his wedding back in 2022. He happened to Google members of the show’s cast, which led him to Joss’ website, where he saw an advertisement for one more entrepreneurial venture: For a few hundred dollars, Joss would perform wedding ceremonies. Right then, Brown hired him.

The ceremony was supposed to take place at the Alamo. Rain forced the couple to relocate to their hotel room, where Joss met them dressed in tight black pants, white cowboy boots, and a scarlet stole. The couple brought along the bride’s father, while Joss brought along his then-wife. Joss placed a pair of moccasins between the couple, symbolizing their journey. “He really incorporated his personal touch into the ceremony,” Brown says. “He turned it into a pretty great experience.” In return, Joss asked for his payment of several hundred dollars and a bottle of Crown Royal Vanilla. While Brown mostly remembers someone who took his role as a wedding officiant seriously, he also saw someone who was troubled. As a minister in a religion called “Dudeism,” inspired by the Coen Brothers film The Big Lebowski, Brown calls himself the “Official Dude” of Texas. When he told Joss about his spiritual work, Joss “took that in a way where he’s like, ‘Oh, I can talk to this guy about my problems.’” He’d call often to vent. About what, Brown will not say, citing religious confidentiality. But Joss, he remembers, said plenty. He was almost dying to be heard.

In a tribute to his friend, Brown is planning to get a new King of the Hill tattoo — this one featuring a shirtless John Redcorn, with one word underneath: “Persevere.”

Jonathan Joss officiating the marraige of Trey Brown and his wife, Laurie.

Courtesy of Trey Brown

THE MAN WHO WOULD SOON FIND find himself at the center of a national debate about hate crimes, homophobia, and what really happened that evening in Texas, Tristan Kern de Gonzales, met Jonathan Joss online, too, having admired his work in Parks and Recreation. On TikTok, he watched Joss throw knives and feed homemade tortillas to his dogs. “I thought the knife-throwing thing was the coolest thing I’d ever seen,” says Kern de Gonzales, 32. “I thought, ‘Why don’t I throw knives in my house?’” Kern de Gonzales reached out to express appreciation, not expecting a response. He got one right away.

That was Jan. 19, 2023. By February, Kern de Gonzales, who lived in South Carolina, was visiting Texas. “He was wearing a beautiful blue dress with a leather jacket and cowboy boots,” Kern de Gonzales recalls of their first meeting. “It was an absolutely iconic look.” The real spark, though, was their conversation. “We both just felt instantly safe with each other,” he explains. “Almost like we had known each other for a long, long time.” He was struck when Joss thanked him for his kindness. “It took me aback,” he admits. “But also it made me start thinking, ‘Why aren’t more people nice to you?’”

Kern de Gonzales didn’t dare imagine, at first, that their bond would be anything more than friendship. “I didn’t even know he had any sugar in the tank,” he says of Joss’s orientation. But he had a suspicion, based on a few suggestive TikTok videos, which was confirmed when Joss started flirting with him. “I was elated,” he remembers, “but at the same time a little nervous.” Kern de Gonzales had to explain that not only was he gay, but trans. He worried about how Joss would react, which he finds silly in hindsight. “You know, we have two-spirit people in the indigenous community,” he remembers Joss telling him, and that was the end of it. “There was no hesitation,” Kern de Gonzales says. “I didn’t feel like I had to be anything other than myself.”

Joss, however, had struggled with defining his own orientation. “It took him a long time to figure out and just come to terms with who he was,” Kern de Gonzales says. Only recently, in the last few years, did Joss begin to embrace his true sexuality. Yet he also told his future husband about performing in drag shows many years before they’d met. They bonded over their shared love of Tina Turner songs. Joss told him he’d worked in gay bars. “He had always been around the community,” Kern de Gonzales says in his steady Southern drawl. “It just took a little bit, I think, for him to find a label and then find acceptance.” Once he did, though, he was very open about it. “Having a faithful spouse who stands by you 100% is worth more than all the money in the world,” Joss posted on May 3. “Never have to worry about where he is and he builds me up. We can handle anything together.”

When Kern de Gonzales moved in with Joss, though, he immediately got a front-row seat to the conflict that, in the days following Joss’ shooting, would be described in local and national news reports. KSAT, the local ABC affiliate, detailed 66 visits to Joss’ home between September 2023 and his death, along with a more specific breakdown: 13 “disturbance neighbor” calls; 10 mental health calls; four wellness checks; and numerous conflicts with Ceja Alvarez, his shooter, in particular. In an interview with the San Antonio Express-News, one neighbor claimed he never heard homophobic insults hurled toward Joss. Long also doesn’t remember hearing anything homophobic when he saw Joss fighting with his neighbors, although he admits most of the flare-ups he saw took place before Joss and Kern de Gonzales were together. Kern de Gonzales, however, describes an atmosphere of rampant harassment of all kinds, including frequent homophobia. He views Joss as a victim of neighbors who tormented him for being different and a local law enforcement apparatus that did nothing to help him. In a statement to Rolling Stone, the San Antonio Police Department’s Public Information Office defended its response. “SAPD officers responded to more than 70 calls for service at Joss’ address,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. “Additionally, the [San Antonio Fear Free Environment] officer assigned to the neighborhood maintained regular contact with both Joss and his neighbors for over a year. The SAPD Mental Health Unit was also engaged and provided additional resources and support.”

Joss and Tristan Kern de Gonzales. “Having a faithful spouse who stands by you 100% is worth more than all the money in the world,” Joss wrote of their relationship.

Courtesy of Tristan Kern de Gonzales

But those interventions were hollow, Kern de Gonzales argues. All show, no substance. “Jonathan would be trying to report through the proper channels,” he says, “but a lot of it was just dismissed because it was easier for them to say, ‘Oh, you’re just high. You’re just hearing things.” Joss was begging to be heard, in other words — but no one was listening to what he had to say.

Then came the house fire, and a video that circulated in its aftermath. The video was filmed that same day in January, when local news trucks showed up to ask about the blaze. At first, Joss blamed himself. He admitted to burning mesquite wood indoors — not in a fireplace — for warmth that morning. “It was my mistake,” he said. “We checked the fire, and we thought there was no fire burning, but evidently there was.” Case closed, argue his critics: He burned down his own house. He said so right there.

Yet the rest of the clip was framed around his ongoing feud with his neighbors. And at one point, he did hint at threats of arson. “I’ve already had neighbors tell me to leave. [That] they’re gonna burn my house down. Call me a fag,” he said. “All these different things.”

The official investigation, a spokesman for the San Antonio fire department tells Rolling Stone, has been closed. He wouldn’t reveal the specific findings, but referred to the aforementioned video. While no criminal charges were filed, it marked the first in a series of bizarre headlines for Joss in the months leading up to his death.

THE COUPLE HAD PLANNED TO LEAVE San Antonio, Kern de Gonzales says. They just needed to pick up a check from a charity for fire victims from Joss’ mailbox, which is why they were there on the evening of the shooting. They were going to use the money to buy a teardrop trailer and drive around the country. “I really try hard not to think about how close we got [to leaving],” Kern de Gonzales says. He finds some comfort in Joss’ rich legacy, including a “historical Western horror” graphic novel that is set to be published posthumously next year in June, for Pride Month. But those final days do linger.

On May 30, two days before the shooting, the couple visited Austin, where a King of the Hill reboot panel was scheduled featuring Mike Judge, the show’s co-creator and star, as well as five other major figures — including main-character voice actors, its co-creator, and the revival’s showrunner. Many other prominent cast members weren’t invited, but Joss felt uniquely left out. “That character, that voice, that story…they were my home, my pride, my connection to something bigger than myself,” he wrote in an April 21 Facebook post. “To not be invited felt like being shut out of a place I helped build.”

So he showed up anyway. About 37 minutes in, he commandeered an audience mic long before the scheduled Q&A had begun. He started with a tribute to Johnny Hardwick, the voice of Dale Gribble, who died of undetermined causes in 2023. But from there, his speech was difficult to follow. He pivoted to the interruption itself: “I see a mic, I use it,” he said. “I see a wrong, I make it right. I want to breathe.” He repeated his claim that his neighbors burned his house down “because I’m gay.” He quoted one of John Redcorn’s most famous songs from the show, “There’s a Hole in My Pocket Where My Money Should Go,” to reference his own dire financial situation. In a play-by-play account of what happened written for Variety, the panel’s moderator later called it “jarring for everyone.”

The next night, at a marijuana-themed venue called the Green Room, Joss appeared on a King of the Hill-themed podcast hosted by a pair of superfans. He explained the panel outburst stemmed from feeling disrespected on behalf of his character, who had come to define him — from his band to his spices to his fame. “When the only thing in my life — other than my husband — I got because somebody else lost their life,” he said, “I kind of owed it to myself to make an asshole out of myself.” Later, the subject turned to his ongoing neighborhood feud. To investigators refusing to “rule out” arson. And to a dark bit of sarcasm. “I would never hurt my dogs. I would never light my dogs on fire,” he said, following up with an apparent joke: “That’s why I shot the little fuckers. And then I burned the house.” One host asked Joss whether he was sober. “No. No. Man, I’ve already lost everything. My house burned down. I ain’t gonna give up drugs,” he said. “I ain’t gonna give up drinkin’. They’re my friends.” The other host remained silent throughout, later explaining in YouTube comments that he was “just watching and soaking it in.” His empathy for addicts, and for Joss’ obvious pain, left him “at a loss for words.”

The next day, Joss would be dead. His shooter, Ceja Alvarez, would claim self defense and deny allegations of homophobia, and his relative would tell the San Antonio Express-News that no one in the family had made homophobic comments to Joss. Ceja Alvarez’s lawyer didn’t respond to Rolling Stone’s multiple requests for comment, but he did speak with KSAT on June 24, arguing that the shooting “has nothing to do with sexual orientation” and that “people in Texas have a right not to be a victim.” His client, he said, had a right to self-defense, and said that “other people know the real truth about the circumstances and the often dangerous behavior” of Joss.

Kern de Gonzales, following his initial statement, has continued to insist the shooting was motivated by bigotry. And while San Antonio police at first rejected the hate-crime allegations, they later walked back that statement, saying it was still too soon to tell.

That night at the Green Room also marked Joss’ final performance. With Rios backing him on guitar, he belted out “There’s a Hole in My Pocket Where My Money Should Go” to several dozen people. “We couldn’t leave without playing that,” says Rios. “There’s a hole in my heart where he used to go.”

Rios also has a video from that night. It shows Joss stomping, grunting, chanting, and shuffling across a stage in cowboy boots and a form-fitting white vest. Without additional context, the video is baffling. But Kern de Gonzales was there, and he saw something beautiful. When Joss was on that stage, tortured as he was, he could be at peace in performance. In what he loved. And in the company of the fans who made it possible. “Everyone was really nice to him,” Kern de Gonzales says. “That’s something that he really, really needed.”

These final glimpses of Jonathan Joss capture what makes his story so unsettling. We crave clear heroes and villains, but Joss embodied contradiction — bringing representation to underserved communities while battling demons; creating memorable characters while struggling to understand himself. His life defies the easy narratives of the internet, challenging us to recognize excellence without excusing behavior. To see humanity without ignoring responsibility. In the space between binary judgments, complicated people leave complicated legacies. And they shouldn’t be remembered by choosing sides, but by embracing the messy reality — something Joss seems to have understood instinctively as he moved through life, always stomping away to a rhythm all his own.